Introduction

The alpha male archetype has long been held up as an aspirational model of leadership – bold, dominant, charismatic, decisive. Drawn from both the animal kingdom and militarised hierarchies, this figure is sold to us in business books, TED talks, political rhetoric, and popular media as the kind of leader who gets things done. But what happens when we stop to examine this ideal – not as nature or necessity, but as a myth? A product?

At its core, the alpha myth reduces leadership to dominance and noise. It equates power with presence, and decisiveness with truth. It flattens complexity and sells performance as substance. But in doing so, it distorts both our understanding of what leadership is – and what humans are.

A Misunderstood Animal

The alpha model is often justified by reference to the animal kingdom. The dominant male in a pack of wolves. The lion who rules the pride. The silverback gorilla no one dares challenge. It’s a metaphor with brute clarity – and it has proven dangerously sticky.

But even this foundation is flawed. The term “alpha male” stems from outdated 1940s research on captive wolves by Rudolf Schenkel. His conclusions were later revised and publicly rejected by wolf biologist David Mech, who found that in the wild, wolf packs function more like family units – led by cooperative, breeding pairs rather than through violence or dominance. Mech wrote, “Calling a wolf an alpha is usually no more appropriate than referring to a human parent as the alpha male or alpha female.”

Contemporary ethology further undermines the alpha myth. Field studies of wolves (Mech, 1999), chimpanzees (de Waal, 2005), and even lobsters (Drews, 2023) suggest that stable hierarchies depend less on aggression and more on grooming, alliance-building, and reciprocity. Dominance without trust collapses quickly.

The Corporate Costume and Historical Rebuttal

In the corporate world, the alpha male becomes not just an analogy, but a role to play. He is confident in every meeting. He fills silence with sound bites. He takes up space. He speaks first and longest. He appears to lead, even when he has no strategy – because the performance is the strategy.

My experience of alpha males in professional life is often marked by arrogance masking insecurity. They believe they’re the smartest in the room – often they’re not. They don’t foster dialogue; they dominate it. They equate certainty with competence, but deliver repetition over progress. Without a strategic framework, they simply rerun yesterday β louder β until the business implodes.

Leadership isn’t about audio volume. And if it were, what would a team be following? A voice, or a direction?

This is where history offers its own quiet rebuttal. Many of the most consequential leaders in history would not meet the textbook definition of an alpha. Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, Angela Merkel, Nelson Mandela, for example – all led through consensus, moral conviction, or clarity of vision. Perhaps the most radical example of all: Jesus Christ, whose legacy was not built on conquest but humility, compassion, and nonviolence.

Sigma Shadows and Military Mythology

The ‘sigma male’ archetype emerged as a counterpoint to the alpha – a lone wolf figure who operates outside the hierarchy but is still powerful. It’s marketed as a kind of outsider genius: silent, strategic, self-made. But this too is a commodified identity. It offers an alternative mask to wear, not a fundamental departure from the same framework of dominance. It romanticises isolation, arrogance, and detachment as enlightenment.

Military metaphors further bolster the alpha myth. The idea of the decisive general who commands clarity in battle appeals to a deep cultural longing for certainty. But real military leadership is collaborative, slow, and systems-driven. In World War II, decisions were made through extensive counsel. Churchill did not act alone. Eisenhower coordinated Allied forces. Strategy emerged from disagreement, delay, and intelligence – not instinct alone.

The fantasy of the ‘one who knows best’ survives because it makes us feel safe. But strategy without shared thinking is just spectacle.

Alpha as Strongman: The UK Political Scene

In the UK, political leadership offers a visible theatre of the alpha myth. When parties descend into chaos, the electorate often longs for a ‘strong leader’ – someone who appears decisive, even domineering.

Boris Johnson embodied the alpha mask. He was brash, performative, quotable. He dominated airtime and reframed politics as entertainment. But behind the showmanship was a pattern of deflection and disorder.

Keir Starmer, by contrast, offers a quiet professionalism. He is often accused of lacking charisma. Boring but steady. Strategic rather than reactive. We can draw parallels with John Major. The contrast is revealing: we say we want strength, but do we mean clarity? Or just noise?

Charisma is Not a Cause and Case Studies in Collapse

The alpha myth rests on the idea that people naturally follow strong individuals. That confidence breeds followers. But in truth, people follow purpose, shared values, or clear plans. The myth enables spectacle. And often, collapse.

- Enron (2001): Jeff Skilling’s ego-driven leadership created a toxic illusion of success.

- WeWork (2019): Adam Neumann’s charismatic chaos expanded the business beyond logic.

- FTX (2022): Sam Bankman-Fried wore the genius hoodie while presiding over fraud.

In all cases, a personality filled the room – but there was no substance behind it. People followed the costume, not the cause.

The Performed vs. Practiced, Ambiguity, Narcissism

Alpha leadership celebrates performance over practice. It rewards fast decisions, loud confidence, and recognisable tropes of strength. But real leadership is quiet. It hesitates. It plans. It listens. It enables others.

The alpha myth also enables narcissism – because its outward traits (charm, dominance, confidence) overlap with narcissistic behaviours. This myth becomes the narcissist’s defence: they’re not dangerous, they’re just leaders.

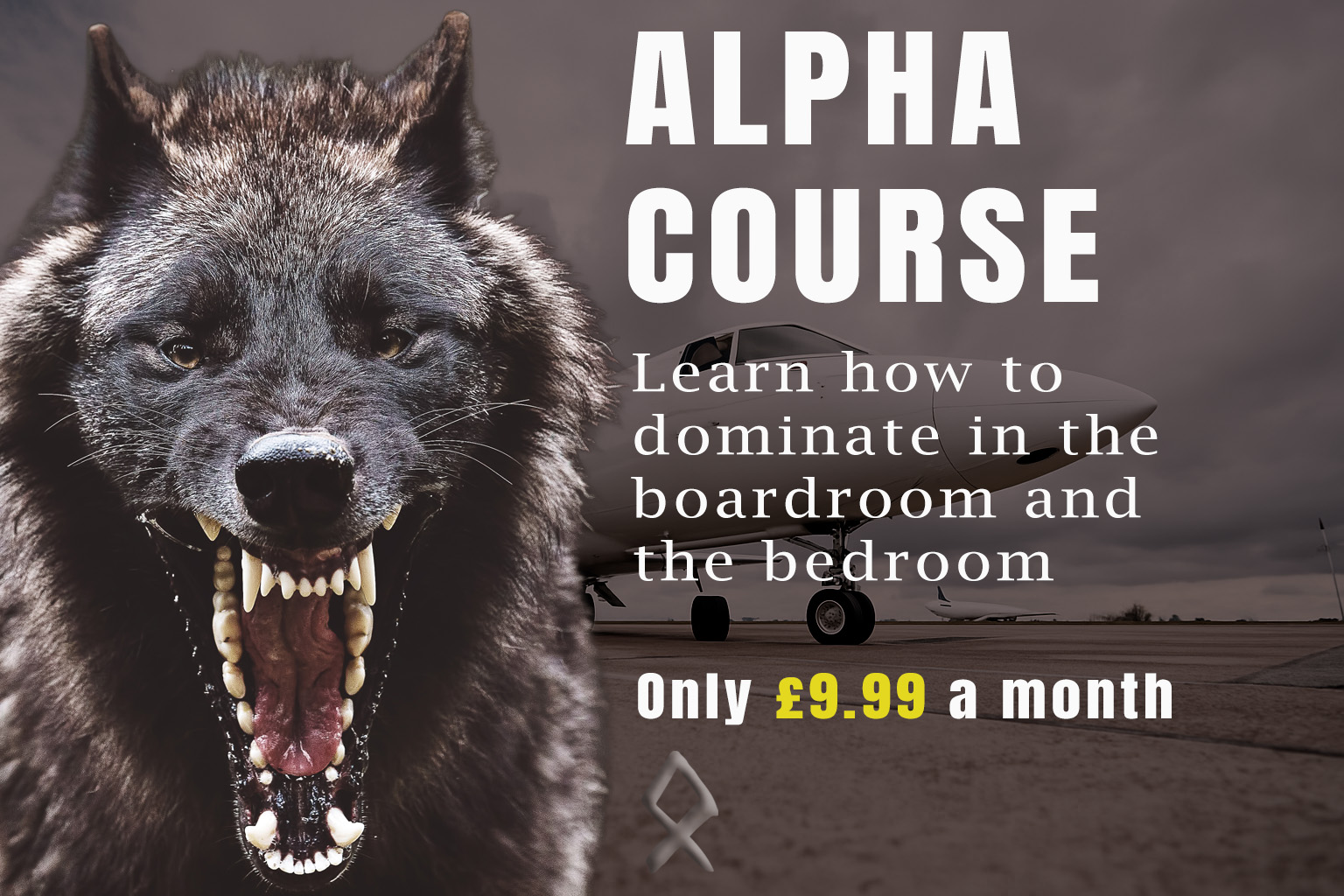

Alpha for Sale: From Leadership Myth to Lifestyle Lie

The alpha male is no longer just a corporate myth or a metaphor from the animal kingdom – it is now a product. A marketable, monetised identity.

Today, online influencers like Andrew Tate, Jordan Peterson, and countless other self-proclaimed ‘real men’ sell the alpha persona as a lifestyle brand. Through YouTube channels, TikTok soundbites, Discord servers, eBooks, and paywalled courses, they tell boys and men: ‘Act like this, and you’ll win.’

The version of success they promote is dangerously narrow: fast cars, gym bodies, financial dominance, and sexual access to women. In this worldview, to be a man is to dominate. To show emotion is to be weak. To listen is to be a beta.

This isn’t just philosophy – it’s a business model. These figures earn from:

- Monthly subscriptions

- Hustle academy programs

- Branded supplements

- Merchandise and affiliate links

Alpha has become a consumable identity. Much like the way Vikings are romanticised and commercialised – stripped of their brutality and repackaged as symbols of masculine glory – the modern alpha is sold as a warrior archetype, designed for insecure times and insecure men.

Social media algorithms reward high-arousal content. Alpha-style messages – polarising, click-driven, emotionally provocative – travel faster and farther. The myth thrives not because it’s true, but because it’s viral.

But it’s not true. Or at least, it is a deeply incomplete story. True leadership, growth, and success come through nuance, collaboration, humility, and empathy. Not through noise and dominance. There is no place in this narrative for enlightenment, it is simply about being and winning in the material world, an identity purchased by a monthly subscription or membership.

The Alpha Cost: Mental Health and Masculinity

This performance has real consequences. The cost of embodying alpha masculinity includes mental health strain, burnout, and isolation. Studies show that men who internalise dominance ideals report higher levels of depression and a lower likelihood to seek help (JAMA Psychiatry, 2020). The alpha mask is heavy – and it cracks.

Intersectionality and the Exclusion Within

It’s important to note that the alpha archetype is overwhelmingly white, cisgender, and heterosexual. Those outside this mould are rarely afforded the same license to dominate.

Alternative Models and Artistic Response

There are better ways to be and to lead. Strategic direction outperforms the single loud voice.

- Patagonia, the American outdoor apparel company, is renowned for embedding environmental and social values into every aspect of its operations. It practices collaborative leadership and reinvests profits to support sustainability.

- Mondragon, based in the Basque region of Spain, is a worker-owned federation of cooperatives. Its democratic structure challenges conventional hierarchies and centres on community wellbeing.

- Buurtzorg, a Dutch healthcare organisation, revolutionised nursing by creating decentralised, self-managing teams that deliver more compassionate and effective care.

- Valve, a US-based video game developer, operates without formal managers. Employees choose projects collaboratively, proving that flat structures can still drive innovation.

- Atlassian, the software company behind Jira and Trello, builds its leadership model on emotional intelligence and psychological safety.

These aren’t utopias. But they work. They challenge the assumption that dominance equals effectiveness. Googleβs Project Aristotle, for instance, showed that psychological safety – not star power – predicts high team performance.

In my visual art practice, I explore these myths of identity and power. The alpha is another identity to suspend. A mannequin, posed, polished, but hollow. In my piece ‘Objects to Suspend Identity’, the mannequin becomes a surface for our assumptions. A stand-in for the leadership myth.

If the system fails when the leader leaves, it was never strong. If no one else is allowed to speak, it’s not leadership – it’s performance. We don’t need alphas. We need vision. We need collaboration. We need silence, sometimes, to hear what’s real.

Bibliography

Scientific & Conceptual Foundations

Mech, D. L. (1999). Alpha status, dominance, and division of labor in wolf packs. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 77(8), 1196β1203. https://doi.org/10.1139/z99-099

de Waal, F. (2005). Our inner ape: A leading primatologist explains why we are who we are. Riverhead Books.

Mahalik, J. R., et al. (2003). Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 4(1), 3β25. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.4.1.3

Wong, Y. J., Ho, M.-H. R., Wang, S.-Y., & Miller, I. S. K. (2017). Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 80β93. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000176

Oliffe, J. L., et al. (2019). Male suicide: A review of risk factors and prevention strategies. Health Sociology Review, 28(2), 141β159. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2019.1624081

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146β1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M. B. F., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F., & Volfovsky, A. (2020). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), 9216β9221. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804840115

Corporate & Political Case Studies

McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (2003). The smartest guys in the room: The amazing rise and scandalous fall of Enron. Penguin.

Brown, E., & Farrell, M. (2021). The cult of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the great startup delusion. Crown Publishing.

Lewis, M. (2023). Going infinite: The rise and fall of a new tycoon. Allen Lane.

Duhigg, C. (2016, February 25). What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

Alternative Leadership Models

Chouinard, Y. (2005). Let my people go surfing: The education of a reluctant businessman. Penguin Books.

Whyte, W. F., & Whyte, K. K. (1991). Making Mondragon: The growth and dynamics of the worker cooperative complex (2nd ed.). Cornell University Press.

Gray, B. H., & Sarnak, D. O. (2016). Reinventing primary care: Lessons from the Netherlands. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/mar/reinventing-primary-care-lessons-netherlands

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations: A guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage of human consciousness. Nelson Parker.

Valve Corporation. (2012). Valve handbook for new employees. https://steamcdn-a.akamaihd.net/apps/valve/Valve_NewEmployeeHandbook.pdf

Atlassian. (n.d.). Team playbook. https://www.atlassian.com/team-playbook