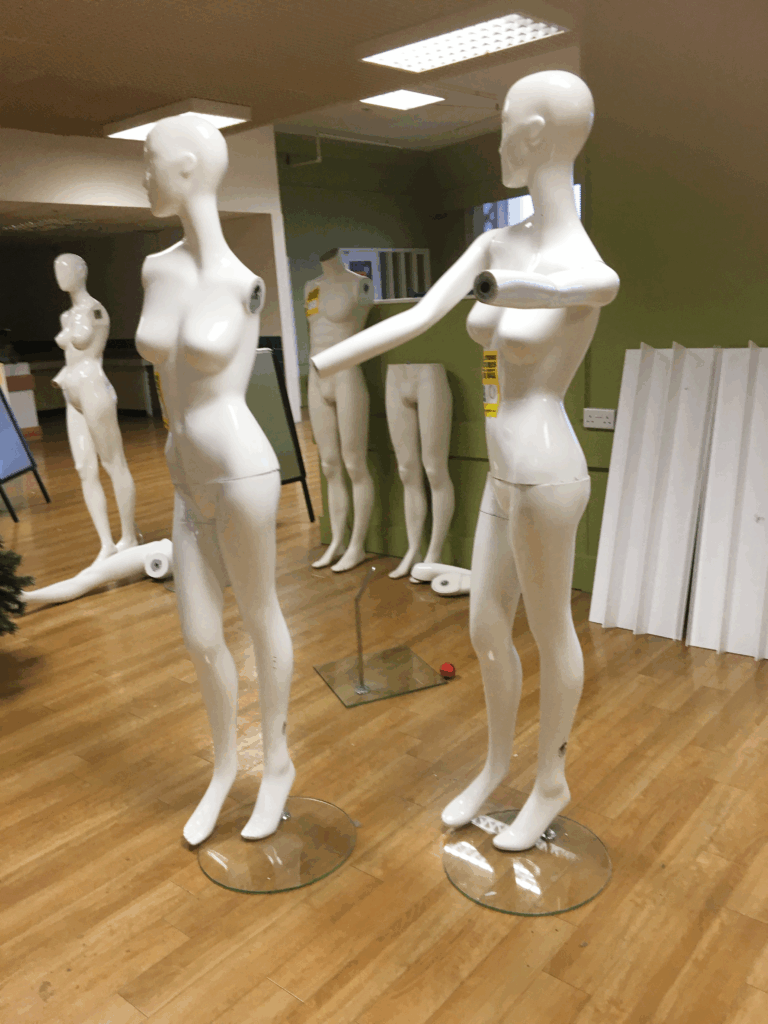

There is a recurring symbol I use in my practice which is a high gloss fibreglass mannequin. I rescued the mannequin on the final clearance, and final trading day of the Debenhams department store in Southsea in 2020.

In the weeks prior, bargain hunters had pretty much stripped the shop of all products, including some fixtures. On the final day the lighting was turned off in sections. A few people seemed to aimlessly browse for a last bargain buy fix. The scene had a post-apocalyptic atmosphere as though it had come straight from the mind of George A. Romero.

The mannequin herself was also on sale. She stood exposed, stripped of all adornment and clothing, missing her hands, and with all her damage visible. Her face was featureless but serene and the high-gloss fibreglass reflected the dim light, giving her an almost celestial glow as she stood observing the shop floor.

In this state and context, I saw the mannequin not as object, but as a witness to end times, to the collapse of the very system that created her.

Adding Movement

A mannequin is, by design, a static object – posed, frozen, and silent. To disrupt this stasis, I added a pair of hospital-issue crutches, sourced from the QA Hospital in Portsmouth. These serve as both a symbolic and practical intervention.

Primarily, the crutches introduce the idea of mobility: a means by which the mannequin – though damaged – can move. She is no longer confined to the shop window or sales floor. With this prosthetic support, she can move through post-consumer landscapes, witnessing collapse elsewhere.

The crutches also act as a second symbol. They are devices associated with injury, fragility, and rehabilitation — a contrast to the mannequin’s idealised body form. Together, they form a contradiction: an ideal supported by a medical aid, beauty on crutches, aspiration assisted.

Connotations and Denotations

The mannequin, with the addition of crutches, is both a remnant of fast fashion, and a witness to the collapse of that system that created her. The mannequin is a silent observer of the “Final Sale.”

The mannequin, traditionally, is a device to sell – a non-person used to animate garments, to project ideals of beauty, and to support consumption through aspiration. In my work, I strip the mannequin of this commercial function and attempt to reassign its role. It becomes a critique – a symbol of consumer collapse, a prop to suspend identity, or even a witness to societal decay.

I place her in contexts stripped of glamour: urban waste grounds, shuttered retail units, derelict or digitally manipulated spaces. No longer an ideal, she is a ghost of one — an echo of desire, dislocated from the systems that once gave her purpose.

In this way, the mannequin enters into dialogue with the world of Slim Aarons. Where Aarons photographed aspirational mid-century lifestyles – sun-drenched tableaux of affluence and ease – my mannequin depicts the aftermath: the hangover of the consumer revolution, the residue left behind.

Audience Projection and Risk of Misreading

During a peer review, I became acutely aware that others may see something very different in my work – especially when they do not share the lived context behind it. My encounter with the mannequin during the Final Sale at Debenhams, and the symbolic associations I assign to her, are not visible to the viewer unless mediated or explained.

Instead, what some viewers may see is a damaged, young, naked, feminine form – positioned, lit, or manipulated in scenes by a stereotypical white man of a certain age. The symbolic intent of my work – critique, witness, aftermath – may be entirely missed. What I read as post-consumer residue, others may read as objectification.

This is uncomfortable, but instructive. It forces me to examine the mechanisms of communication in my practice – and to question how meaning is constructed, challenged, or lost.

I’m left asking:

- Am I relying too heavily on my own lived experience to anchor meaning?

- Am I doing enough to bridge that experience for the audience – through titling, framing, or contextual clues?

- Are some objects – especially those already saturated with cultural meaning, as in a mannequin – too defined to be effectively reinterpreted?

These questions remain open, but essential. They inform how I present this work moving forward, not to dilute its message, but to ensure or test its criticality is accessible and its ethics are considered.

Providing a context bridge

The tension between intention and perception is vital. A work’s meaning can be overlooked, misunderstood, or interpreted through entirely different lenses than the artist intended – sometimes negatively. This isn’t always a failure, but it is a risk, particularly when dealing with charged symbols like the mannequin.

One way to navigate this is through the supporting structure of presentation – titles, artists’ statements, exhibition design, or even curation itself can act as a kind of context bridge, helping the viewer step closer to the intended reading.

Alternatively, I’ve begun to consider whether the story of the mannequin – the act of finding her, rescuing her, and reassigning her purpose – could be presented as a standalone artwork or text piece. The mannequin could be exhibited physically, displayed within a glass case, alongside a narrative or archival-style label detailing her “biography”: where she came from, the moment she was found, and how she has since travelled through works. She could be given a birth and death date – transformed from discarded retail prop into symbolic artefact.

As a curatorial gesture, this could serve as a grounding element for a wider exhibition exploring themes of consumerism, identity, disposability, and memory. The mannequin becomes both origin story and anchor – a conceptual spine for the viewer to return to.

Key Questions Moving Forward

- How do I ensure my intent is visible, without over-explaining or neutralising ambiguity?

- Can framing (titles, wall text, artist statement, exhibition context) do the heavy lifting?

- Should the mannequin be named, archived, documented — treated as a collaborator rather than a prop?