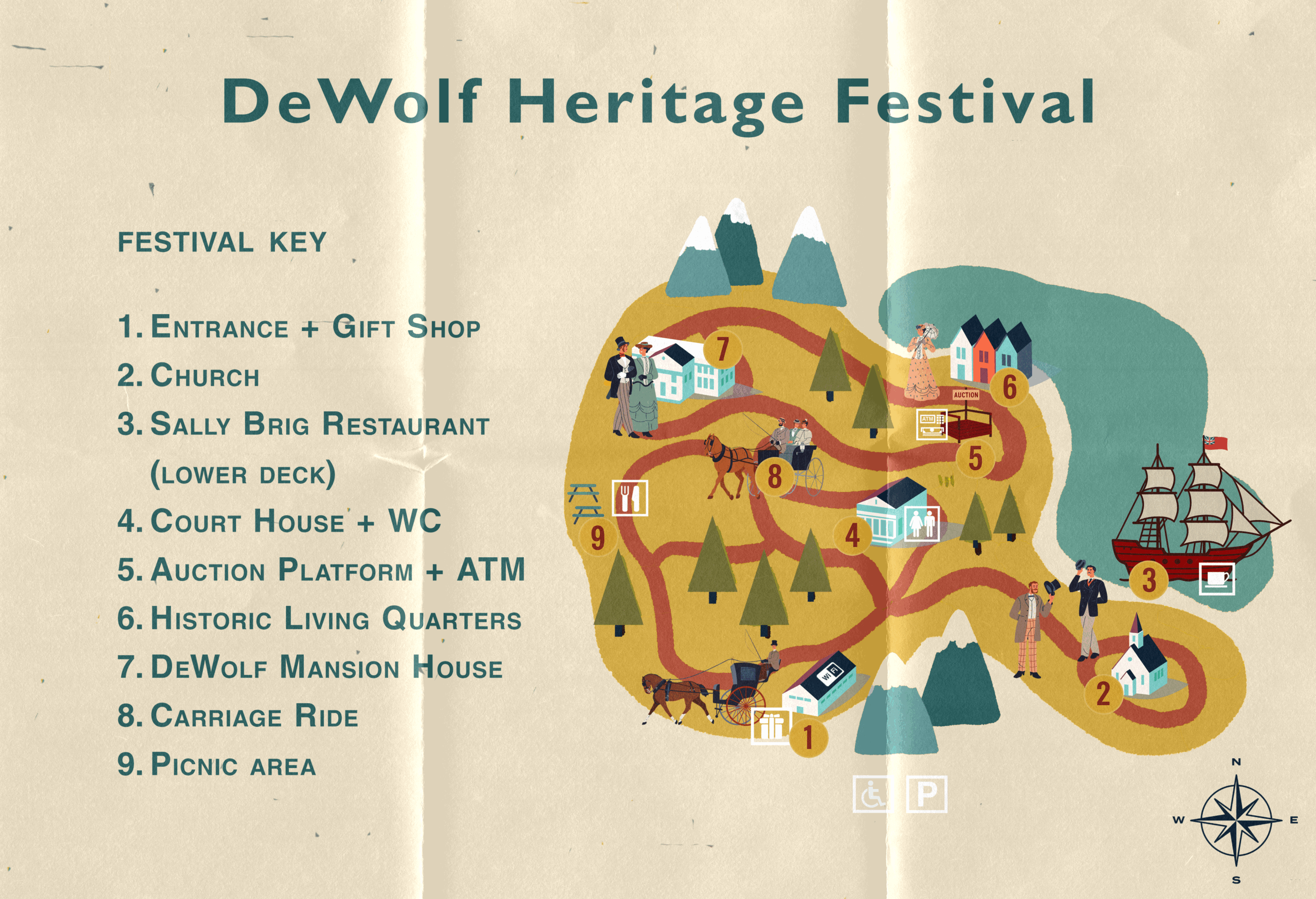

The DeWolf Heritage Festival Map is a critical artwork exploring format as both tool and weapon ─ in this case, the cheerful festival map, typically associated with leisure, family fun, and regional pride. This format is reappropriated to interrogate the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade, with a specific focus on the DeWolf family of Bristol, Rhode Island ─ one of the most prolific slave-trading dynasties in American history, rooted not in the South, but in the North.

The DeWolfs were responsible for over 80 slaving voyages between 1769 and 1820, transporting more than 10,000 Africans to the Americas. Their ships, including the notorious Sally, made repeated crossings of the Middle Passage, exchanging rum and goods for human lives. The family’s wealth helped fund banks, churches, and cultural institutions that still exist today.

In this map, the enslaved are not shown. Their absence is not accidental ─ it mirrors the deliberate omissions of the past. In much of the historical documentation produced by slave traders, enslaved individuals were listed as cargo, not people. They were counted, priced, and insured like barrels of sugar or bolts of cloth. Their lives did not matter. Auction stands are marked here, as are stately homes and waterfront docks ─ but the human suffering that enabled them remains hidden.

The legacy of the DeWolf family has itself been publicly questioned by descendants. In Traces of the Trade, a 2008 documentary and memoir by Katrina Browne ─ a DeWolf descendant ─ family members retrace the triangle trade and confront the uncomfortable truth of their inherited history. Notably, most of the wealth generated by the trade did not endure; those who bear the name today did not necessarily inherit privilege, but they did inherit a legacy. That legacy, like the map, is unevenly distributed, filled with gaps, absences, and uncomfortable truths.

The installation format is crucial to the piece. The printed map is folded and placed casually on a camping-style festival chair, positioned atop a one-meter square of artificial grass. This gesture references contemporary festival culture, evoking picnics, open-air music, and curated “heritage” experiences. By couching atrocity in the language of leisure, the work asks: What is remembered, what is omitted, and what happens when we allow marketing formats to shape historical memory?

The DeWolf Heritage Festival Map questions not just history, but how history is sold ─ and who gets to do the selling. It invites the viewer to unfold a version of the past that was never meant to be seen.